What possibilities are there for realizing true interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research collaborations across the boundaries of the natural sciences, the social sciences and the humanities? The initiative Inscribing Environmental Memory (IEM) is putting this question to the test. IEM is an unfolding experiment in integrated environmental studies that draws together scholars from literature, archaeology, anthropology, history, geography, geology and life sciences. Together with its sister project Comparative Island Ecodynamics (CIE), IEM anchors the Circumpolar Networks program of IHOPE (Integrated History and Future of People on Earth), one of the core projects that make up the Future Earth global initiative for the advancement of sustainability science. IEM’s interdisciplinary and longue durée approaches strongly reflect the principles of historical ecology as pioneered by researchers such as CBM’s Carole Crumley.

If we truly wish to come to terms with the implications, and potential complications, of human-environmental interactions in the future, we would do well to understand those of the past at various temporal and geographical scales. Drawing on the rich vein of medieval saga literature unique to Iceland, the IEM initiative seeks to improve our understanding of how Icelandic communities of the past understood and coped with environmental change by looking not only within but also across periods of known change and considering human-environmental interactions through time as ”completed experiments of the past” (Dugmore et al). These are not esoteric questions that concern only the distant past. They are among the most pressing questions of the present and near future. Coming to terms with the human dimensions of environmental change turns out to be far more complex than early earth system sciences and resilience theory researchers imagined. Understanding how past societies responded to social-ecological risks or regime shifts may help us better navigate present and future challenges in an era of accelerated environmental transformation. The global change research field is a scientific domain that begs contributions from many specialized fields of knowledge, not least from the humanities and social sciences.

Crossing Disciplinary Borders

The research collaborations that have come together in the IEM initiative are defined by a radical openness to disciplinary border crossing that aligns physical environmental studies with aesthetic, ethical, historical and cultural modes of inquiry. This kind of approach allows for multidisciplinary crowd-sourcing of data and expertise concerning questions of common interest. It also enables more fully integrated investigations based on co-design and co-execution of problem-based research questions, as well as co-dissemination of results to the extent that this is now possible.

Evidence from written sources compiled in Iceland over many centuries has significant potential to improve our understanding of the human dimensions of long-term environmental change. The story of human ecodynamics during the first thousand years of Icelandic history is one of losses and gains for the environment, one of successes and failures for the human communities that adapted to, and with, that environment. This history raises many interesting questions concerning the interdependency of social and ecological factors. In some ways Iceland provides a fascinating laboratory for comparing anthropogenic and non-anthropogenic environmental change on various scales (millennial, centennial, decadal or even interannual in some instances, thanks to technical dating advances such as tephrochronology). Iceland was settled in the Viking Era (late 9th century) by people deriving primarily from the region known in modern times as Scandinavia, with significant migration from the British Isles. Though we may be inclined to think of Icelanders as transplanted Europeans it is worth noting that the ancestors of modern-day Icelanders settled a pristine environment centuries before the Inuit ancestors of modern-day Greenlanders migrated to Greenland. In this sense Icelanders are very much an aboriginal people whose culture has evolved while adapting to a changing environment.

The environment of the island underwent significant anthropogenic changes following the rapid and large-scale process of Icelandic settlement in the 9th and 10th centuries. Subsequent transformation of the landscape for new uses makes Iceland a very interesting test case of pre- and post-human influence on pristine ecosystems and landscapes. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, which have witnessed alarming trends in biodiversity loss due to human activities around the world, it has become something of a commonplace to think of anthropogenic environmental change as linked to alarming species losses. With the arrival of human beings there more than 1100 years ago, Iceland actually witnessed the opposite–a significant increase in biodiversity, through the intentional introduction of numerous domesticated fauna (sheep, goats, cattle, horses, and pigs) and the unintended introduction of other species (rodents, flora and a great many new insect species). Some of these anthropogenic influences became key drivers of subsequent vegetation changes and extensive soil erosion, ultimately resulting in a reduction of native birch woodlands from pre-human levels by 95%, leaving only one per cent of the total land area covered by this once prolific species in modern times (Biological Diversity in Iceland).

Iceland’s remarkably well preserved indigenous record of local human responses to social-environmental changes may be unique in the circumpolar north for its historical depth and close attachment to specific places. These written sources allow us to look at roughly a thousand years of documented history and compare available information to other bodies of evidence from archaeology, geological sciences and life sciences. Such written sources are not only a valuable repository of proxy data about historical changes to natural systems; they can also provide us with insights concerning how Icelandic society has memorialized, preserved and transmitted local ecological knowledge over many generations–what is referred to as ”environmental memory” in the IEM initiative. The literature in its most self-consciously rendered forms (as in the sagas) offers immensely valuable contextual information concerning communities embedded in their landscapes and timescapes, human inhabitants animated in their social, economic, and environmental milieux through narratives that both contain and transmit vital cultural knowledge. This kind of qualitative resolution helps to endow physical evidence of environmental changes following first human settlement with a fluidity and dynamism that are the very essence of historical reconstruction.

”Skallagrim was an industrious man. He always kept many men with him and gathered all the resources that were available for subsistence. (…) He had a farmstead built on Alftanes and ran another farm there, and rowed out from it to catch fish and cull seals and gather eggs, all of which were there in great abundance. There was plenty of driftwood to take back to his farm. Whales beached there, too, in great numbers, and there was wildlife there for the taking at this hunting post; the animals were not used to man and would never flee.”

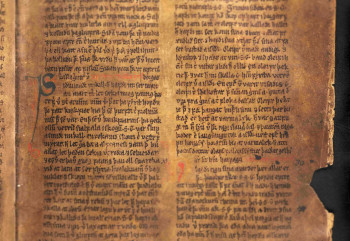

”Skallagrim was an industrious man. He always kept many men with him and gathered all the resources that were available for subsistence. (…) He had a farmstead built on Alftanes and ran another farm there, and rowed out from it to catch fish and cull seals and gather eggs, all of which were there in great abundance. There was plenty of driftwood to take back to his farm. Whales beached there, too, in great numbers, and there was wildlife there for the taking at this hunting post; the animals were not used to man and would never flee.”The photograph shows folio 73 recto from the 14th century Möðruvallabók (AM 132 fol.), showing a part of Egils saga Skallagrímssonar. One has to be careful not to take this passage at face value because it contains some conventional elements that can be found in other stories as well. This is one important argument for integrating literary studies into an interdisciplinary environmental studies project such as IEM. Generally scientists may not be so well versed in literary texts, literary history or critical analytical methods. Working collaboratively with literary critics can help them distinguish between different varieties of information in terms of what elements may be considered more or less reliable.

Foto: Photograph provided by the Árni Magnússon Institute for Icelandic Studies. Photographer: Jóhanna Ólafsdóttir.

Unique Literary Sources

Literacy in the vernacular developed early in Iceland as a result of the circumstances by which Christianity became established there from the 11th through the 13th centuries. This in turn led to the production and preservation of an exceptionally rich written record early in the country’s history. These sources include early historiographical works; medieval annals; geographical descriptions; legal records; parish registers; merchant’s records; landowners’ accounts; governmental reports by local officials; livestock inventories, ecclesiastical charters; census deeds; price lists, tribute-payment agreements; and other written works of poetry, biography and saga literature.

The sagas are perhaps the most famous Icelandic export from the medieval period. There are in fact numerous different genres of saga literature, though the so-called Sagas of Icelanders are the best known outside Iceland. For the most part these sagas present recognizable places and plausible social situations, as well as historically grounded events and figures that would have been regarded by native audiences in the pre-industrial period as a part of their society’s shared past. The question of whether the sagas are reliable accounts of the past or fictional narratives has animated saga scholarship for a long time and remains to some degree a subject of popular debate. The Sagas of Icelanders are now regarded primarily as works of literature, though based upon historical events and characters. Although written in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, they describe events that occurred two to three hundred years earlier during the so-called ”Saga Age” from around AD 930 to 1030. Among other things, the sagas contain descriptions of the environmental conditions encountered by the settlers, and many accounts of how the island’s natural resources were used and exploited by their descendants (Hartman et al).

A long-term historical focus informed by critical humanities scholarship and social science research has been underrepresented in previous research on global change. IEM and kindred research collaborations now unfolding under IHOPE Circumpolar Networks are working actively to change this situation. This is far from a simple task. In joint investigations that attempt to integrate expertise, methods and data from across scientific domains that have previously lacked a history of collaboration, high transaction costs can be expected, not only in formulating research questions, but also in planning and executing studies, and finally in addressing the outcomes to diverse end users. For this reason, in recent years interdisciplinary summer field schools closely affiliated with the CIE and IEM projects have been organized for doctoral students by NIES, NABO and the Svartarkot Culture-Nature project in Iceland to help build cross-disciplinary literacies and research capacities. The models of integrated study and knowledge synthesis that are foregrounded in these courses reflect a developing sense of the potentialities gradually being realized in the projects. These advancements may bring their own distinct value to future research collaborations.

Icelandic sagas

The Icelandic word saga comes from the verb ”segja” (to say or tell), which means ”to tell a story.” The term also denotes its own genre of literature, the Icelandic sagas. The sagas were written by hand on vellum in Old Norse/Old Icelandic and reproduced by hand in numerous manuscript copies. The medieval Icelandic sagas encompass numerous sub-genres such as the Kings’ sagas, notably Heimskringla, a compilation of tales of the Norse rulers stretching back from historically based Viking Age figures to mythical forerunners, or the Legendary sagas such as Volsunga saga (whose tale of Sigurd the dragon slayer was popularized in Wagner’s Ring cycle). Other important genres from a historical vantage point include the so-called Contemporary sagas (as found in the Sturlunga compilation) and the Bishops’ sagas concerning twelfth and thirteenth century secular and religious leaders and conflicts between prominent families during this period. The most famous saga genre is the Icelandic Family Sagas, now usually referred to as the Sagas of Icelanders.

Inscribing Environmental Memory

IEM is a collaboration of the Nordic Network for Interdisciplinary Environmental Studies (NIES) and the North Atlantic Biocultural Organization (NABO). Participating research groups come from the Nordic countries, the United Kingdom, and North America. As a complement to the international project Comparative Island Ecodynamics (CIE), funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation, IEM anchors the Circumpolar Networks program of IHOPE (Integrated History and Future of People of Earth), a core project of Future Earth.

IEM can best be described as a confluence of research collaborations that explore historical environmental change through cross-cutting, team-driven studies from multiple knowledge communities and scientific domains. Because it straddles the fence between a large project and a cohesive program, it may be more useful to think of the initiative as a scholarly community of practice. Affiliated researchers whose work may have contributed, directly or indirectly, to this article include: Astrid Ogilvie, Thomas McGovern, Andrew Dugmore, Jón Haukur Ingimundarson, Árni Daníel Júlíusson, Viðar Hreinsson, Reinhard Hennig, Vicki Szabo, Megan Hicks, George Hambrecht, Richard Streeter, Adolf Fridriksson, Michael Twomey, Emily Lethbridge, Árni Einarsson, Ragnhildur Sigurðardóttir, Karen Milek, Ramona Harrison, Gísli Sigurðsson, Orri Vesteinsson, Þorvarður Árnason, Gísli Pálsson, Jim Woollett, Jette Arneborg, Konrad Smiarowski, Frank Feeley, Sophia Perdikaris, Anthony Newton, Christian Koch Madsen, Mae Kilker, Phil Buckland and Steven Hartman.